Frostflower and Thorn and also Windbourne: Worldbuilding, inside and out

Phyllis Ann Karr's Frostflower and Thorn and Frostflower and Windbourne were published in 1980 and 1982 respectively. The sorceress Frostflower and warrior Thorn hail from the Tanglelands, the kind of gritty, dangerous pseudo-Medieval European fantasy setting that is very much at home in the eighties and which is seeing a resurgence in the aughts and teens of this century. (If the descriptors "gritty," "dangerous," and "pseudo-Medieval" remind you of anything, Frostflower and Thorn begins with a note that it was first written during George R. R. Martin's Clarke College workshop in 1977.)

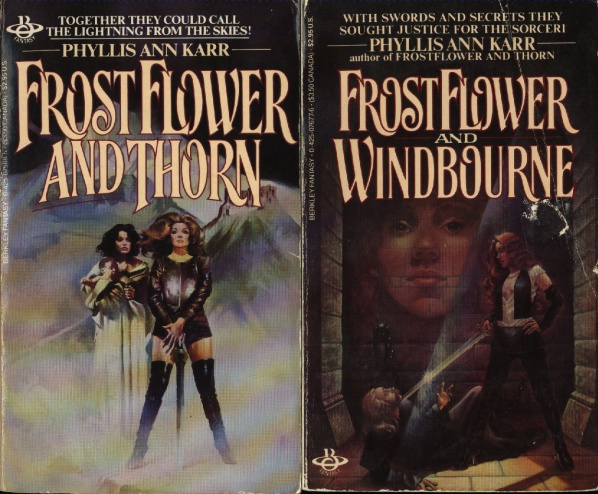

Paperback edition covers. Ms. Karr said Thorn on the Windbourne cover looked like a dominatrix.

What I love the most about the Frostflower books is the worldbuilding. The setting is familiar in some ways, but still new enough to be interesting. There's a dominant polytheistic religion where fertility gods and their "farmer-priests" are exalted (the priests are not actual manual laborers--they have people for that--but more like feudal lords and fertility priests combined), and a minority monotheistic religion that is the subject of much suspicion and frequent persecution. The adherents of the latter are called sorceri, and have supernatural powers over such things as time or weather. Sorceri practices smack of Catholic monastic life in some ways--geographic seclusion, celibacy, knowledge of technology and science, even the black robes the faithful wear when going abroad. There are significant differences, too, such as their gender egalitarianism. And the magic, of course.

The dominant society ruled by the farmer-priests, or "farmer's folk" as the sorceri derisively call them, have far more rigid gender roles. The most visible and unusual of these, and one that had some feminists at the time mistaking the Tanglelands for a female-dominated world according to Karr, is that the warrior class is entirely female. There's no "woman warrior" or "warrioress" business here, since that would be redundant. Though there was no mention of married warriors (though I imagine some are married), unattached warriors have full sexual freedom including access to other women's husbands as "warrior's privilege." I don't know if the "privilege" applies over the men's objections since in the one scenario where it was invoked the man was quite willing.

In another interesting wrinkle, both the story and the author in her notes make it clear that the Tanglelands are not gender-egalitarian, far less matriarchal. The farmer-priests who hold both spiritual and temporal power are polygamous men, with priestesses ruling only in rare cases such as a priest dying without any male heir. The crafts and businesses are for the most part the realm of men. This means men control politics, religion, and money, while women are largely their wives, dependents, or expendable hirelings. The warrior Thorn reflects at one point that men are used to thinking they are important as individuals, while women learn that what matters is not who they are as people but what service they provide. This gets interesting when you think about the predominance of men in our own world's military and police, though the configurations of gender and prestige are different enough that it's not a straight inference of anti-men sexism. Sorry, MRAs.

Those are the externals of this world, but for me the most interesting and important aspect of the Frostflower books is the way this world works from the inside--that is, in the characters' minds and actions. Faith and codes of conduct are not just points on an information sheet for Karr's characters, but form the actual bedrock of how they see their world and their places in it. This is especially clear when characters forgo what seem like universal goods--power, safety, even life itself--in accordance with their worldviews. Things like religion and social custom are not just lip service but fundamental bedrocks of their world, an internal dimension of worldbuilding that makes the externals meaningful.

Since I'm steering clear of spoilers in this analysis, let me give an example that doesn't give the plot away: In the Tanglelands throwing spears are for outlaws and thieves, not warriors in good standing. Though the reason is not explicitly given, it's clearly related to codes of honor and social standing, not tactical advantage. It's probably premised on the thinking that warriors should have skin in the game when it comes to other honorable warriors--you take the risk of injury and death and don't just fell them at a safe distance. Obviously, as with any rule unscrupulous individuals can and do twist the rule when it's to their advantage, but breaking firm social rules comes with consequences of its own.

It's easy to think we're past this kind of thing now, that we live in an age of rationality where we don't give up clear advantages for superstition and outdated custom. However, as Francis Fukuyama points out in The Origins of Political Order, even assuming we all aim to maximize advantages we first need a framework to determine what those advantages are in the first place. Worldviews provide that framework, a way to give meaning to our choices and place ourselves in the world. The kind of internal worldbuilding that Karr does so well in the Frostflower books provides perspective on how our own choices and perspectives in real life are affected by cultures and paradigms (which is in a whole different zip code from saying they are inauthentic or wrong). This is exactly the kind of service fiction should provide.

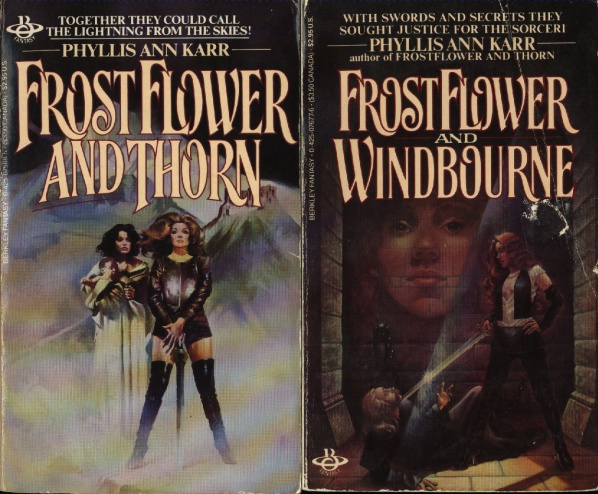

The e-book covers. Pro: No dominatrix in sight. Con: Nothing of any interest whatsoever in sight.

Arguably, though, the primary service of fiction is to be entertaining and on this point the books deliver solid but mixed performances. Don't get me wrong, both books are thrilling and fun to read, especially the first book Frostflower and Thorn. I loved the titular characters, who are both products of their respective traditions and yet individuals in their own right. I came to care deeply for both these women in all their complexities and general awesomeness, not to mention the friendship that grew up between them.

(Warning! The next paragraph makes statements about the plot of the book in broad terms and may be considered spoilery. Skip it if you don't want any hints about crucial plot developments.)

Thorn also deserves praise for not pulling its punches. The story actually uses the nastiness in the world it built, religious persecution, a justice system that is medieval in every sense of the word--instead of backing away from its own premises and relegating them to the safe closet of "stuff that never happens to characters who actually matter." This makes for harrowing reading at times, but it's a testament to the book's quality that it doesn't descend into a pornography of human suffering. Even in the most painful moments all the characters are human: The victim is not an object to disengage from and gawk at, nor are the perpetrators mustache-twirling villains who are evil for the sake of evil. This sense of balance and proportion in the face of difficult subjects is a rare feat, and shows real moral courage as well as skill on the part of the author. I would recommend it for that reason alone.

(End slightly-spoilery bits. You can look now.)

The major flaw that mars both books is their pacing: The occasional diversions into aspects of the world, and worse, the teeth-grinding way characters think and argue about every possible angle of every action. It's admirable that the author put so much thought into all the possible contingencies, but that's no reason for readers to suffer along. These incessant debates grew obnoxious toward the climax of Thorn when I was on the edge of my seat about what was going to become of the characters I cared about, but found myself entangled in arguments about whether it was a good idea to tie a character's hands and all the reasons for and against. I thought the book ended well on a thought-provoking and moving note, but getting there was exhausting for the wrong reasons.

Though I consider Thorn the stronger work, its sequel Frostflower and Windbourne actually suffered less from pacing problems because it was the quieter, more introspective book. Though there is a murder mystery thrown in, Windbourne is not very plot intensive and focuses more on changes in the characters and the world. That helped me overlook the way the story got bogged down in details in a way I couldn't for the dramatic sequences in Thorn when a good pace was crucial to enjoyment. The characters and world that commended Thorn to me are still present in Windbourne, though, so both books were worth a read for me.

Don't expect much from the character Windbourne, by the way. He's well... not an afterthought, maybe, but definitely incidental compared to the leading ladies. I am happy to report that the second book is also very much a Frostflower and Thorn show. The author herself wonders in her notes if she should have titled it "Frostflower and Thorn II" or "Frostflower and Thorn Meet Windbourne," which indeed may have been better. Ah, hindsight.

I took a chance on the Frostflower duology based on the strength of Karr's other work (The Idylls of the Queen, an Arthurian murder mystery starring Sir Kay as the sleuth, and The Arthurian Companion, an encyclopedia of Arthuriana) and was not disappointed. The uniqueness of the world and the unflinching storytelling are not only good in themselves but have more currency than ever at a time when gritty fantasy is back in vogue. I really think the works and the world they are based on are overdue for introduction to a broader audience. Their availability in ebook format is a good start, and their greatest weaknesses are of the sort a good adaptation could easily take care of. These underrated books are hidden gems that I hope will be newly discovered, decades after first publication.

Paperback edition covers. Ms. Karr said Thorn on the Windbourne cover looked like a dominatrix.

What I love the most about the Frostflower books is the worldbuilding. The setting is familiar in some ways, but still new enough to be interesting. There's a dominant polytheistic religion where fertility gods and their "farmer-priests" are exalted (the priests are not actual manual laborers--they have people for that--but more like feudal lords and fertility priests combined), and a minority monotheistic religion that is the subject of much suspicion and frequent persecution. The adherents of the latter are called sorceri, and have supernatural powers over such things as time or weather. Sorceri practices smack of Catholic monastic life in some ways--geographic seclusion, celibacy, knowledge of technology and science, even the black robes the faithful wear when going abroad. There are significant differences, too, such as their gender egalitarianism. And the magic, of course.

The dominant society ruled by the farmer-priests, or "farmer's folk" as the sorceri derisively call them, have far more rigid gender roles. The most visible and unusual of these, and one that had some feminists at the time mistaking the Tanglelands for a female-dominated world according to Karr, is that the warrior class is entirely female. There's no "woman warrior" or "warrioress" business here, since that would be redundant. Though there was no mention of married warriors (though I imagine some are married), unattached warriors have full sexual freedom including access to other women's husbands as "warrior's privilege." I don't know if the "privilege" applies over the men's objections since in the one scenario where it was invoked the man was quite willing.

In another interesting wrinkle, both the story and the author in her notes make it clear that the Tanglelands are not gender-egalitarian, far less matriarchal. The farmer-priests who hold both spiritual and temporal power are polygamous men, with priestesses ruling only in rare cases such as a priest dying without any male heir. The crafts and businesses are for the most part the realm of men. This means men control politics, religion, and money, while women are largely their wives, dependents, or expendable hirelings. The warrior Thorn reflects at one point that men are used to thinking they are important as individuals, while women learn that what matters is not who they are as people but what service they provide. This gets interesting when you think about the predominance of men in our own world's military and police, though the configurations of gender and prestige are different enough that it's not a straight inference of anti-men sexism. Sorry, MRAs.

Those are the externals of this world, but for me the most interesting and important aspect of the Frostflower books is the way this world works from the inside--that is, in the characters' minds and actions. Faith and codes of conduct are not just points on an information sheet for Karr's characters, but form the actual bedrock of how they see their world and their places in it. This is especially clear when characters forgo what seem like universal goods--power, safety, even life itself--in accordance with their worldviews. Things like religion and social custom are not just lip service but fundamental bedrocks of their world, an internal dimension of worldbuilding that makes the externals meaningful.

Since I'm steering clear of spoilers in this analysis, let me give an example that doesn't give the plot away: In the Tanglelands throwing spears are for outlaws and thieves, not warriors in good standing. Though the reason is not explicitly given, it's clearly related to codes of honor and social standing, not tactical advantage. It's probably premised on the thinking that warriors should have skin in the game when it comes to other honorable warriors--you take the risk of injury and death and don't just fell them at a safe distance. Obviously, as with any rule unscrupulous individuals can and do twist the rule when it's to their advantage, but breaking firm social rules comes with consequences of its own.

It's easy to think we're past this kind of thing now, that we live in an age of rationality where we don't give up clear advantages for superstition and outdated custom. However, as Francis Fukuyama points out in The Origins of Political Order, even assuming we all aim to maximize advantages we first need a framework to determine what those advantages are in the first place. Worldviews provide that framework, a way to give meaning to our choices and place ourselves in the world. The kind of internal worldbuilding that Karr does so well in the Frostflower books provides perspective on how our own choices and perspectives in real life are affected by cultures and paradigms (which is in a whole different zip code from saying they are inauthentic or wrong). This is exactly the kind of service fiction should provide.

The e-book covers. Pro: No dominatrix in sight. Con: Nothing of any interest whatsoever in sight.

Arguably, though, the primary service of fiction is to be entertaining and on this point the books deliver solid but mixed performances. Don't get me wrong, both books are thrilling and fun to read, especially the first book Frostflower and Thorn. I loved the titular characters, who are both products of their respective traditions and yet individuals in their own right. I came to care deeply for both these women in all their complexities and general awesomeness, not to mention the friendship that grew up between them.

(Warning! The next paragraph makes statements about the plot of the book in broad terms and may be considered spoilery. Skip it if you don't want any hints about crucial plot developments.)

Thorn also deserves praise for not pulling its punches. The story actually uses the nastiness in the world it built, religious persecution, a justice system that is medieval in every sense of the word--instead of backing away from its own premises and relegating them to the safe closet of "stuff that never happens to characters who actually matter." This makes for harrowing reading at times, but it's a testament to the book's quality that it doesn't descend into a pornography of human suffering. Even in the most painful moments all the characters are human: The victim is not an object to disengage from and gawk at, nor are the perpetrators mustache-twirling villains who are evil for the sake of evil. This sense of balance and proportion in the face of difficult subjects is a rare feat, and shows real moral courage as well as skill on the part of the author. I would recommend it for that reason alone.

(End slightly-spoilery bits. You can look now.)

The major flaw that mars both books is their pacing: The occasional diversions into aspects of the world, and worse, the teeth-grinding way characters think and argue about every possible angle of every action. It's admirable that the author put so much thought into all the possible contingencies, but that's no reason for readers to suffer along. These incessant debates grew obnoxious toward the climax of Thorn when I was on the edge of my seat about what was going to become of the characters I cared about, but found myself entangled in arguments about whether it was a good idea to tie a character's hands and all the reasons for and against. I thought the book ended well on a thought-provoking and moving note, but getting there was exhausting for the wrong reasons.

Though I consider Thorn the stronger work, its sequel Frostflower and Windbourne actually suffered less from pacing problems because it was the quieter, more introspective book. Though there is a murder mystery thrown in, Windbourne is not very plot intensive and focuses more on changes in the characters and the world. That helped me overlook the way the story got bogged down in details in a way I couldn't for the dramatic sequences in Thorn when a good pace was crucial to enjoyment. The characters and world that commended Thorn to me are still present in Windbourne, though, so both books were worth a read for me.

Don't expect much from the character Windbourne, by the way. He's well... not an afterthought, maybe, but definitely incidental compared to the leading ladies. I am happy to report that the second book is also very much a Frostflower and Thorn show. The author herself wonders in her notes if she should have titled it "Frostflower and Thorn II" or "Frostflower and Thorn Meet Windbourne," which indeed may have been better. Ah, hindsight.

I took a chance on the Frostflower duology based on the strength of Karr's other work (The Idylls of the Queen, an Arthurian murder mystery starring Sir Kay as the sleuth, and The Arthurian Companion, an encyclopedia of Arthuriana) and was not disappointed. The uniqueness of the world and the unflinching storytelling are not only good in themselves but have more currency than ever at a time when gritty fantasy is back in vogue. I really think the works and the world they are based on are overdue for introduction to a broader audience. Their availability in ebook format is a good start, and their greatest weaknesses are of the sort a good adaptation could easily take care of. These underrated books are hidden gems that I hope will be newly discovered, decades after first publication.